Waltonwood Resident Shares Prison Camp Experience

Cary, NC – Tens of thousands of people were held in prison camps by Imperial Japan during World War II. One of its survivors shared her family’s story living in the camps with fellow residents at Waltonwood Cary Parkway.

Little Known History

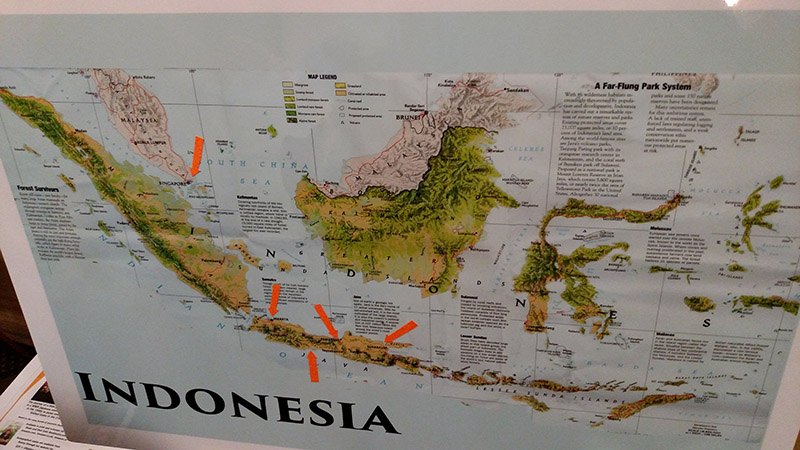

Ronny Herman de Jong was three years old when Japan invaded the island of Java, then part of the Dutch East Indies colony, and put her and her family into a prison camp for women and children. Because she was so young, and because she said her mother hid her from most of the atrocities, Herman de Jong said she only has three clear memories of her time there: the spread of bed bugs and their smell when they died, a Japanese guard thrusting a bayonet blade into a fence and nearly hitting her head and the day some male prisoners moved to their camp.

“This old man gave me a toy. It was a dinky little toy truck but I loved it because we didn’t have any toys in there,” Herman de Jong said. “That was a nice memory.”

For most of her information about life in the camps, Herman de Jong relied on a diary her mother wrote in the camps for her two books about their experiences: “In the Shadow of the Sun” and “Rising from the Shadow of the Sun,” which she drew on for her presentation at Waltonwood Cary Parkway on Tuesday, August 15, 2017. Herman de Jong said her mother’s diary, which was written in the style of letters to her family back in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands, is an important historical document she wanted to share with people.

“Everyone knows about the Holocaust and they know about the battles against Japan at Iwo Jima and Midway the Battle of the Coral Sea,” Herman de Jong said. “But I was a little girl in a concentration camp and almost no one knows about these camps. The Japanese army held civilian prisoners and tried to kill them.”

So Herman de Jong not only published her books, as well as the anthology “Survivors of WWII in the Pacific” about other prisoners’ experiences and the stories of veterans who fought in the Pacific theater in World War II, but has been giving talks about her family in the camps everywhere she has lived. Now that she has moved to Cary in the past three months, living at Waltonwood, she wanted to do the same here.

“Even younger Japanese people don’t know as much about the war crimes,” Herman de Jong said. “Japanese people are nice but it has been kept out of history books. When I lived in Hawaii, I met with Japanese-Americans and spoke about my book at a Rotary Club meeting. You could hear a pin drop as I talked. No one had a bad thing to say about it.”

Experience During the War

Herman de Jong’s father was in the Dutch Naval Air Force so she and her family – mother, father, one younger sister – lived on Java at a base in Surabaya. When the Japanese Imperial Army invaded, people were separated into camps, with women and children put together. It was there that Herman de Jong stayed for around three and a half years with her mother and sister.

She estimated 8,000 people were living in her camp, with people kept in four-person homes 40 people at a time. Women in her camp had to do hard labor, as well as dig their own latrines and clean out the waste. Her sister got so weak, Herman de Jong said she looked like a skeleton by the end.

“Many people were put together so tropical diseases would spread and prisoners would die,” Herman de Jong said. “These were death camps.”

No communication went in or out of the camp so despite Imperial Japan surrendering on August 15, 1945, prisoners were only freed from her camp on August 23. And at that point, Indonesian nationalists were armed by the Japanese and they were killing Dutch people as they began to fight to end colonization.

Later in life, Herman de Jong would see declassified memos to Japanese soldiers stationed at these camps near the end of the war. One was telling guards to flee in order to escape prosecution for war crimes, another was to kill all prisoners “without leaving traces.” This discovery led her to write the follow-up book “Rising from the Shadow of the Sun” and to talk more about her mother’s life, who lived to be 101 years old.

“I had to write about it,” she said of the Japanese memos. “If I didn’t know about it, other people didn’t know either.”

In the intervening years, Herman de Jong has lived back in the Netherlands, lived in California, Hawaii, Arizona and now Cary, and even went back to Java in 1993 and saw the prison camps where she lived now turned into a neighborhood.

“There is no trace of the horrible things that happened there,” she said. “But my mother made everything easy for a little child. Whatever happened to me, as long as mamma was around, I was happy.”

Herman de Jong’s books about her family’s experiences and about World War II in the Pacific are available online.

Story and photos by Michael Papich.

My mother and I, her sister and her two children were just like Ronnie and her mother and siblings put in these camps. We were from Bandoeng but my mother had traveled to Surabaja to be with her dister who was pregnant and had lost her husband fighting the Japanese. He lost his life on Dec. 14, just six days into war on the submarine the o16. We were taken to Moentilan and later to Banjoebiroe 10. My mother hardly spoke about that time. it was to painful. Both sisters were raped by the officers in camp. They struggled the rest of their life with these horrible atrocities inflicted on them. I do have all Ronnie books. I wrote my memoirs as well. During my life as a teenager I could not understand my mother, but later in life, bit by bit I got to know more. She started to tell me. My book is called “I Thought You Should Know.” Under my maiden name Thea T van der Wal.