Cary History: Walter Hines Page – The Ambassador

Cary, NC – In the third and final chapter in our series on one of the most famous people to ever come from Cary, Walter Hines Page, we take Page from his nation-wide fame as a provocative journalist to international notoriety as he became the ambassador to Great Britain at a key point in global history.

Out of Print and Into Politics

In our last piece, Page had mostly left North Carolina to continue work as an editor and publisher in New York and New England. He would return to the state periodically to give speeches, mostly about the importance of public education and he wrote that he considered it to be his true home.

But in the North, Page edited the Atlantic Monthly, established Doubleday, Page and Company Publishing House and published and bought major magazines and newspapers. This increased his place as a top influential figure in the United States.

Page decided to use that influence to push for Woodrow Wilson to become President of the United States. If you remember from the previous story on Page, as a reporter for The New York World, he reported on news in Atlanta and part of that assignment led to him striking up a good relationship with Wilson.

Wilson was elected in 1912 to become the 28th President (27th if you consider that Grover Cleveland is typically counted twice) and Page had the ear of the country’s new leader. One such example was Page’s advice that Wilson deliver the State of the Union address in person, rather than via letter as had previously been done. And as any high school Social Studies student who is assigned to watch the speech will tell you, it is now an established tradition for the president to address Congress in person every year.

Division Between Two Nations

In the Wilson White House, Page was appointed to be ambassador to Great Britain. That fit Page well, given his years studied and traveling Britain and Europe as a young man and his love of Shakespeare, and he was well liked by British officials.

His relationship back home changed significantly once World War I broke out in 1914. Wilson did not want the United States to enter the war and hoped the Allies and Central Powers would wear each other out and eventually negotiate a peace. Page saw the war as German military power vs. British culture, or as he put it, a battle “to exterminate either English civilization or Prussian military autocracy.”

While Page’s push for the United States to enter the war only made him more popular in Britain, getting honorary degrees from Cambridge, Oxford, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, it caused a significant rift between Page and Wilson. In Page’s first return to the United States since getting his post as ambassador, Wilson confronted him personally and “in action and words he displayed the most severe dissatisfaction with Britain and British policy.” Despite Wilson eventually reaching a point where he did not feel he could trust Page’s objective judgment on Britain and the war, he never pulled Page from his position.

In 1917, the United States eventually entered the war. Page ended up barely living through the rest of the war, dying of heart failure in Pinehurst on December 21, 1918, one month after Armistice.

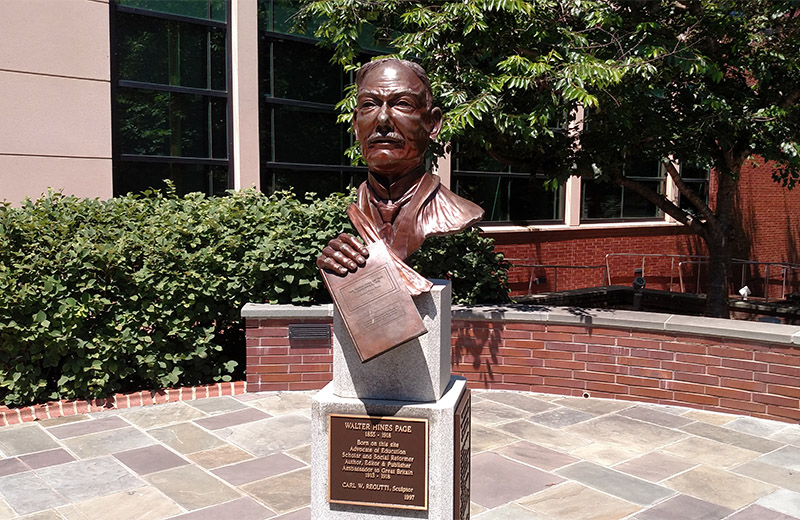

Page’s Recognition

Walter Hines Page has gone on to have several prominent remembrances after his death. Cary High School, NC State, Randolph-Macon College, Johns Hopkins University and Duke University all have buildings or schools named after him. Page is one of only three Americans with a plaque at Westminster Abbey, his reading “The friend of Britain in her sorest need.”

Page’s acclaim grew in his immediate death following a series of biographies commissioned by his family. Two of which, The Life and Letters of Walter Hines Page and The Training of An American, won author Burton Hendrick Pulitzer prizes.

In the first full-length biography of Page since Hendrick’s, John Milton Cooper Jr.’s Walter Hines Page: The Southerner as American, served as a link between Southern and Northern values that “shed a light that reached a long way down the road that finally ended with Jimmy Carter in 1976.”

Story by Michael Papich. Sources: “Around and About Cary” by Thomas M. Byrd, “The Superfluous Ambassador: Walter Hines Page’s Return To Washington 1916,” published in The Historian by Ross Gregory and “Walter Hines Page, Intersectional Ambassador,” published in The Southern Literary Journal by Rayburn S. Moore.