Cary History: Walter Hines Page – Education and Mummies

Cary, NC – In the second of three stories about Cary’s favorite son, Walter Hines Page, we follow Page’s transformation from a young rabble-rouser from a large family in Cary to a force for reform and consternation statewide as he worked his way through the ranks of prestigious newspapers and magazines.

Letters From Home

When we last left Page, he had decided a career in journalism would be more effective at spreading his ideas and messages about Southern reform and Jeffersonian Democracy than being a teacher. However, his penchant for critiquing the Confederacy and other problems he saw in Reconstruction-era North Carolina meant no state newspapers would hire him.

So instead, Page left to write for the St. Joseph Gazette in Missouri. He started as a reporter in January 1880 and by Autumn, he was already editor.

This gave Page enough reputation and financial stability to leave the paper and become a traveling writer for big city newspapers nationwide. He went through the South, writing letters and essays about what he saw, crafted for a Northern audience. One of his most well-known articles was an interview with former President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, who was then living in Mississippi.

The popularity of Page’s letters landed him a secure job with The New York World, where he became the literary editor and also worked on assignments such as reporting on Atlanta events and meeting Woodrow Wilson, whom Page took a shine to.

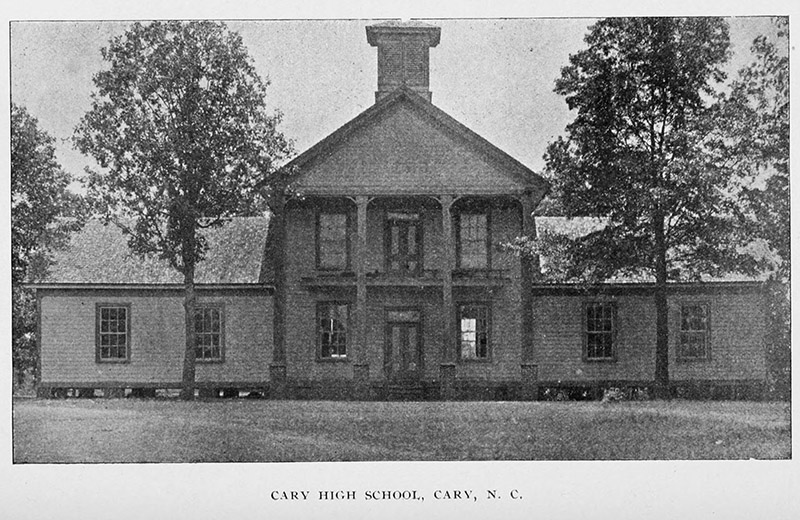

Cary High School, 1896. In 1922, the school created a building for vocational training and named it the “Page building.”

Fighting for Public Education

Instead of staying in New York, Page wanted to return to North Carolina to, as R.D.W. Connor put it in The Journal of Social Forces from 1924, “arouse her out of her lethargy – to start her forward on the road of social, economic, and political progress.” In 1883, Page returned and bought the struggling Raleigh newspaper The State Chronicle, working as its editor.

With his new position of power, Page campaigned for public education in North Carolina. The existing system had badly deteriorated after the Civil War. He later expanded this idea to include public vocational training schools after investors from New England told him cheap labor was pointless if workers were uneducated and unskilled.

Page’s fight for education continuously hit walls of opposition. He attributed much of the criticism to members of the General Assembly he said only got elected because of their military service as part of the Confederate army. So from then on, The State Chronicle broke from the style of newspapers in North Carolina and refused to address these elected officials by their military rank. In his articles, Page would refer to these Confederates and others who stood in the way of education as “mummies,” comparing them to the dried-out old pharaohs recently uncovered by archeologists.

This made Page increasingly unpopular in North Carolina and he ended up selling the Chronicle in 1885 but continued to send letters to the paper, mainly on the subject of the “mummies” and their opposition to public schooling.

“Let ’em alone. The world must have some corner in it where men can sleep and sleep and dream and dream and North Carolina is as good a spot for that as any” – Walter Hines Page

While Page left for the North after selling the Chronicle, he was invited back to give speeches at universities and other institutions, where he repeatedly said a lack of investment in education was responsible for North Carolina’s economic woes, which caused as much divided opinion in the state as any of his other endeavors.

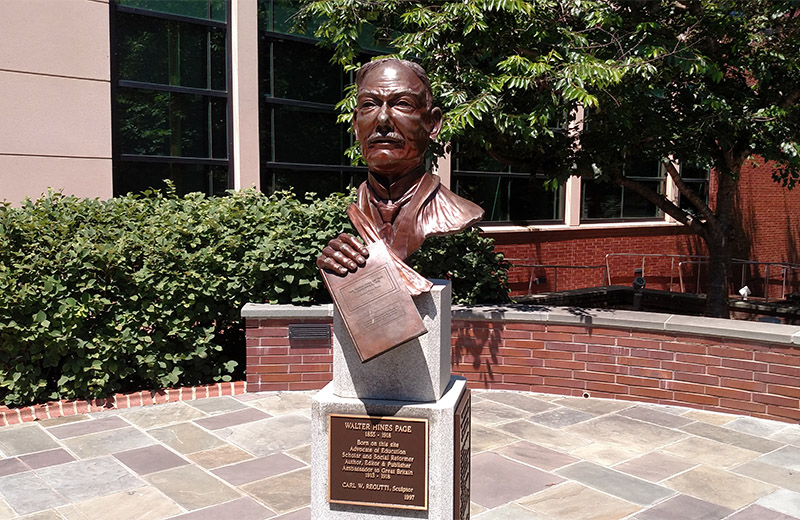

Impact on His Home

While Page mostly lived in the North after 1885, he continued to express affection for his home. In his semi-autobiographical novel “The Southerner,” Page wrote of his character Nicholas Worth that North Carolina was “the Old Place” and “the Old Place was the background of my life, therefore, a sort of home back of my home.”

Even after his departure, Page’s campaign for public education continued. His letters brought attention to the issue of education, and by 1887, the General Assembly passed legislation for a public vocational school that would go on to become NC State.

Page also altered the course of North Carolina journalism by selling the Chronicle to Josephus Daniels. When Daniels was 22, he was part of the young, progressive demographic Page’s Chronicle spoke to and wrote that “it seemed to call to rise above all hindering traditions.”

Daniels would go on to spread the influence of his newspaper across North Carolina and the United States as a whole, even becoming the head of the family that would go on to own The News and Observer.

Outside of North Carolina, Page also made big strides in the world of newspapers and publishing. He became the first non-New Englander to become an editor for Atlantic Monthly, turned around the failing magazine Forum and was part of the establishment of Doubleday, Page and Company. Doubleday would go on to become one of the largest publishing houses in the country, starting influential magazines such as World’s Work and pioneering how photographs were used in newsprint.

Not all of Page’s fights were successful, however. As editor of the Chronicle, he urged Southerns to turn away from fried foods and we all know how that turned out.

In Part 3, we’ll look at how Page’s meeting with Wilson in Atlanta led to him eventually becoming one of the most important people in America during World War I.

Story by Michael Papich. Sources: “Around and About Cary” by Thomas M. Byrd, “The Southerner” by Walter Hines Page and “Walter Hines Page: A Southern Nationalist,” published in The Journal of Social Forces by R.D.W. Connor.